By: Ben Hurley, Master of Marine Policy, 2024

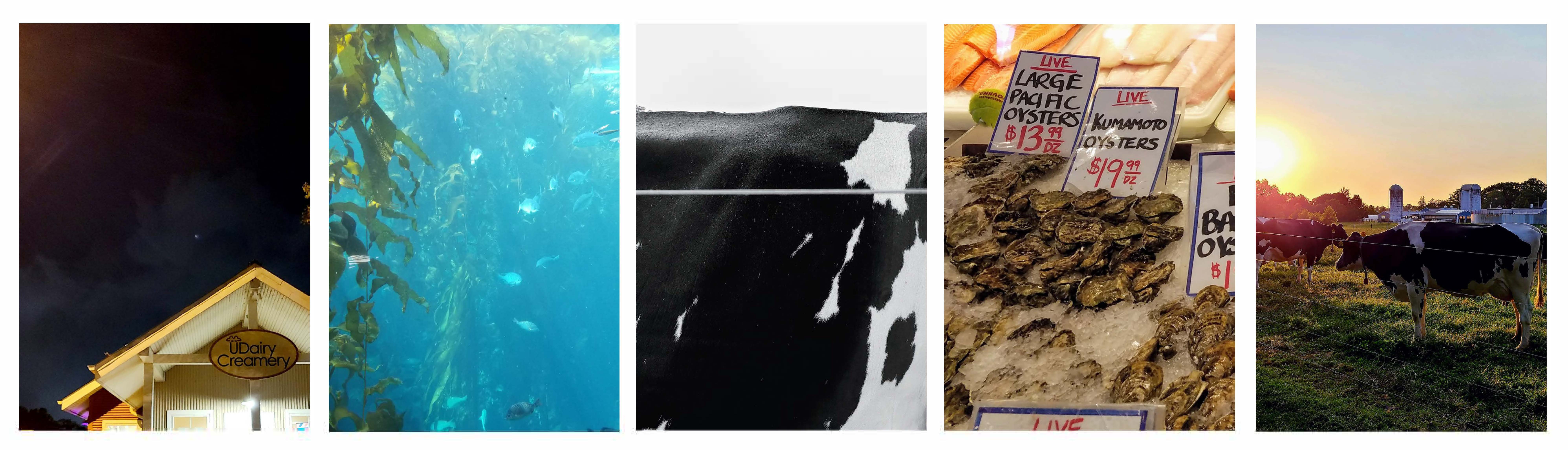

In my two short years at the University of Delaware, my research has undergone a few changes. In the spring of 2023, I found myself trudging up a gravel path to interview the UD Dairy Operation about their cows. In the spring of 2024, I completed my master’s degree after defending a research project on shellfish permitting in Washington state. The path from cows to clams had its twists, but it was nothing if not enriching.

I entered the Master’s in Marine Policy program with a background in marine science. My research experience was largely limited to analyzing fish guts, and the idea of designing a policy-based research question was daunting. I was unsure of even where to start in picking a research question that was worth studying: meaningful in some way, yet able to be tackled by a novice researcher. An elusive balance.

With just two years to work with, my advising team and I hit the ground running. My courseload was frontloaded with classes heavy in economic research methods so that I could quickly develop the skills needed for my project. Dr. Birkenbach’s course in Natural Resource Economics and Dr. Oremus’ course in Environmental Economics complemented one another to teach me foundational theory and methods of analysis in the policy field. Other classes taught me to code in Stata (a common programming language) and to use regression analysis to put these methods into practice.

More important, however, were our first advising meetings to discuss my research interests. In those first semesters, Dr. Birkenbach, Dr. Oremus, and I slowly distilled amorphous areas of interest into the first glimmers of a research question. I was interested in aquaculture policy, so we gravitated toward the seaweed farming industry, an understudied area in the United States. My advisors connected me with people close to the industry, and informational interviews with academic researchers, seaweed farmers, and even an ocean-based venture capitalist gave me the background I needed to start asking better questions. Not a research question, maybe, but questions targeted enough to guide me through the (sea)weeds of the academic literature.

That literature search, in turn, is what finally led me to delve into the policy basis for seaweed’s use as livestock feed. It was an interesting idea, and as a bonus, I got to see UD’s cows.

However, research is complicated, and obstacles arose. The livestock feed research path closed because its unknowns lay more in the logistics of processing facilities than of policy. A separate foray into an economic valuation of the nascent seaweed industry was more suited for a large economic firm than a graduate researcher. For many other seaweed- and shellfish-related ideas, the data needed simply did not exist.

The ensuing workshopping of my research question was an invaluable education. As we debriefed each new hiccup in my weekly advising meetings, I understood better and better where to look next in our search. I turned from seaweed to shellfish—an adjacent but much more established industry—to take advantage of the increased data availability. A major court case in Washington struck me as sharing some features with the economic studies we’d read about in our classes, and I found a dataset to pair with it. I had the ingredients to a proper research project at last.

My second year was a similar whirlwind to the first. Even with a dataset at my disposal, now our advising meetings shifted to sorting out the snags and bumps of numbers, analysis, and research design. Throughout these meetings, I continued to learn from the extensive experience of my advisors. I learned about the publishing process firsthand as we wrote and submitted a short paper, and I assisted and observed Dr. Oremus in her long-term fisheries research for the Natural Resources Defense Council. However, as supported as I felt by my advising team, I also felt entrusted with being in the driver’s seat of the project. My work felt like my own, born out of my own interests and education. Over the course of my degree, I could see myself growing as a researcher.

The result was my analytical paper: “Quantifying the Evolving Influence of Environmental Variables on Shellfish Permitting Timelines in Washington.” By analyzing data on shellfish operations from the Army Corps of Engineers, we dove into a major legal challenge to the shellfish and began to tease apart the influence of critical ecological factors on the industry’s permitting process. It was a messy process getting there, and it is certainly not perfect, but I was proud to defend it to my academic committee.

I am incredibly grateful to Dr. Oremus and Dr. Birkenbach for their continued support over these two years. Their hands-on approach ensured that I had the tools I need to succeed in my work while developing the independence, resilience, and ingenuity to take on policy questions in years to come. As I head into law school this fall, I have no doubt my experience at UD will open new doors for me in coastal policy. And if some of those doors involve cows again, I’ll be ready for them.